Today marks the 150th anniversary of the single bloodiest conflict ever witnessed on American soil. The Civil War’s Battle of Antietam, fought 60 miles outside of Washington D.C., resulted in the death of 23,000 Union and Confederate soldiers in just 12 hours—a statistical horror never replicated again in any conflict fought within the United States.

The Battle of Antietam marked the first time the Union substantially halted a string of Confederate advances into the North. Looking back, historians conclude the victory allowed President Lincoln to issue the Emancipation Proclamation—fundamentally altering the context of the nation’s conflict, and thus, our understanding of the battle’s importance.

Were a battle of this magnitude to erupt today, we would know about it within seconds—breaking news alerts would buzz in our pockets, anchors would interrupt our regularly scheduled programs and social media would drill down on the latest details of the rapidly evolving situation. Often, we intake news imagery before knowing all the details, and in the early hours following the conflict, we might not know the full meaning of what occurred, but we definitely know what it looked like.

One hundred and fifty years ago, on the other hand, the public viewed painfully explicit photographs with unconditioned eyes—the first time America visually confronted the carnage of its conflict.

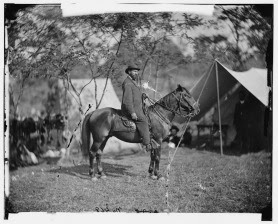

After the Battle of Antietam, photographer Matthew Brady tacked a sign to the door of his New York City photo studio that read, simply, “The Dead of Antietam.” Inside, he exhibited the work that his assistant, Alexander Gardner, made in the aftermath of the inconceivably bloody fighting at Antietam Creek. The show drew a large crowd.

One particular viewer, Oliver Wendell Holmes, took notice of Gardner’s photographs, and in an 1863 issue of the Atlantic Monthly, penned his reaction. “It is not [for viewers] to bear witness to the fidelity of views which the truthful sunbeam has delineated in all their dread reality,” he writes. “The sight of these pictures is a commentary on civilization such as the savage might well triumph to show its missionaries.”

Holmes writes of the dreadful accuracy with which Gardner’s photographs depict the gruesome casualties of war. Photography, less than 50 years old in 1862, was still understood by many as an extension of painting. Early critics were often split between a view of photography as objectively accurate or grossly inaccurate and incapable of matching the magnitude of the scenes it recorded (either for want of detail or of a ‘correct’ perspective).

Holmes, it seems, falls in the latter camp. As an eyewitness to the Battle of Antietam, he bristles at the idea that the public may, after viewing Gardner’s work, presume to understand the true nature of war. He mentions that the emotions came flooding back to him as a witness to the scenes captured by Gardner—emotions that he would like to lock in the recesses of a far-off place. Holmes feels that this pictorial representation, while succeeding in capturing the physical setting of war, does nothing to convey the visceral nature of conflict among men that he witnessed. Yet he still acknowledges how the public is moved practically to tears as they realize the implicit significance of Gardner’s photos. Although they don’t understand what he feels as a witness, they are moved in ways they shouldn’t be afforded as mere casual viewers of recorded conflict.

The New York Times echoed Holmes’ chilly wonder at how captivating Gardner’s war photographs seemed. The paper noted that the public response to Gardner’s images was as if the photographer had “brought bodies and laid them in our dooryards and along the streets.”

“You will see hushed, reverend groups standing around these weird copies of carnage…chained by the strange spell that dwells in dead men’s eyes,” they write.

Images of today’s conflicts still arrest us just as they did in 1862. We pause, marveling at their vibrancy, viciousness and pictorial excellence. The world of 2012 allows us to “like” them, “share” them, and “re-tweet” them, hoping to pass along to others the feelings they elicit in us.

Gardner’s pictures articulated a different utility. Depicting the dead fathers and sons of a generation, his plates represent one of the first times America was forced to confront its own tragedy—emotionally—immediately after the fact.

While today we perceive and employ the Antietam photographs as memory triggers and historical records, the public of 1862 confronted them with no expectations or precedent. Unconditioned (and perhaps not yet protected by) the daily and hourly cataract of imagery that we endure today, Civil War-era viewers recognized Gardner’s images for what they were: immediate reminders of the brutal nature of mankind. And thus, on the 150th anniversary of the bloody conflict at Antietam, it’s worth pause to consider how the modern image of conflict impacts us.

>

>

Source: Time

No comments:

Post a Comment